Finding the evidence

The investigation and fact-finding alliance is called the 5AM Coalition, in a nod to the time on February 24 when life in Ukraine was upended by the sound of Russian missile strikes across the capital Kyiv.

Working closely with prosecutors, group members have been poring over about 750 cases, gathering testimony, and archiving videos and photos from social media.

Bakery attack

One of the investigations concerns an attack during March in Chernihiv, northern Ukraine. People standing in line outside a bakery were shelled, and 14 of them died. A Ukraine public TV station called Suspilne captured video of the aftermath that went viral. Inspections and eyewitness interviews found there were no military targets in the area at the time.

The Russian military immediately denied any involvement. Igor Konashenkov, the Russian Defense Ministry spokesperson, said the victims had been killed by Ukrainian terrorists – or the video was faked by Ukraine’s Security Service (SBU).

A painstaking process

Investigators started by trying to identify the weapon that caused the blast. They analyzed shell shards from the site and determined that they were fired from 152-millimeter self-propelled howitzers: long-range weapons designed to launch artillery shells towards an enemy tens of kilometers away.

Shell pockmarks show the direction they came from. Roman Avramenko, executive director of Truth Hounds, a human rights organization that belongs to the 5AM Coalition, determined the attack was launched from the northeast. Investigators then worked to pinpoint the launch site.

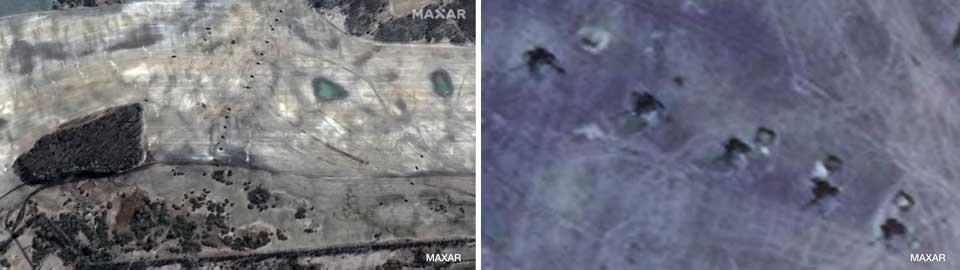

Everything came together when satellite images of the pinpointed location showed several howitzers deployed on the day of the incident. Avramenko was able to identify shadows that the barrels cast on the ground, which showed they were pointed towards Chernihiv.

Finally, eyewitnesses corroborated sightings of Russian troops at the launch site. The weapons used were identified as belonging to the Russian Armed Forces.

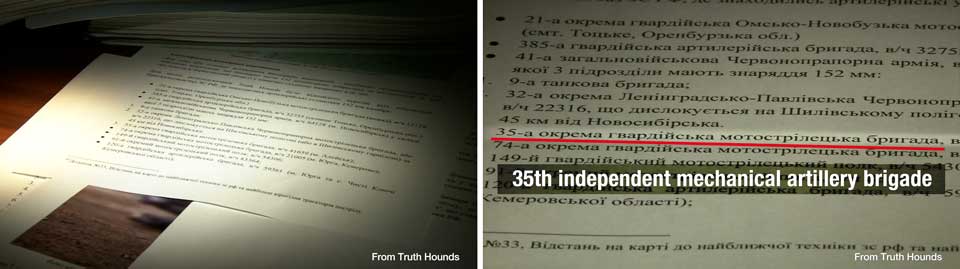

Investigators dug deeper to find which brigade was deployed to the site. Studying internal documents and online information about the Russian military, as well as lists of Russian bases with howitzers, they were able to identify the brigade responsible.

Prosecution

The work into the bakery attack took four months, and the evidence it unearthed is now before the Ukraine Prosecutor’s Office.

Avramenko says investigations like this one would be possible with both open-source information and people on the ground by cross-referencing each other.

“From my experience, no open source solely can replace the part of field work,” he says. “We know how valuable it is to talk directly with witnesses, observe the place, and collect all the pieces of information. Of course, we need to complement this with open-source intelligence to build a link.

“Justice will be possible because of this kind of work. Everything’s thoroughly collected, kept and investigated.”

The Ukrainian Prosecutor’s Office is establishing a system to work with groups like the 5AM Coalition. “Open-source material like photos and video is collected using specific methods for us to use later in court,” explains Yuriy Belousov, Ukraine’s chief war crimes prosecutor. “It is now one of our main information sources.”

Ukraine a game changer

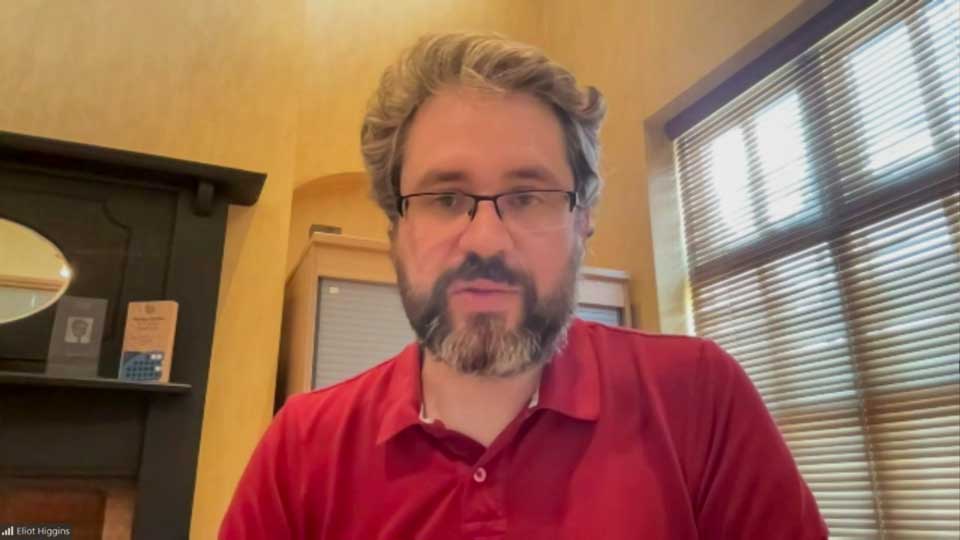

Open-source research pioneer Elliot Higgins, the founder of investigative group Bellingcat, says the Ukraine crisis has raised the profile of open-source research.

“When this conflict started you had a community come together around the invasion that was debunking fake news very, very rapidly. In any conflict, open-source evidence has definitely become of increasing value,” he says, noting the combination of investigative skills on the ground with sources like satellite imagery and other information is “something that’s changed dramatically over the last couple of years.”

International Criminal Court accepts open-source evidence

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the European Union has amended its regulations to allow judicial authorities to use open-source evidence on war crimes, including satellite images, photos and videos taken by civilians, in cases before the International Criminal Court.

Higgins points out it can be challenging to use open-source evidence in the courtroom, although it is rapidly becoming mainstream: “We’ve now got better and better investigating it to a point where we can actually turn it into a process that is focused on legal accountability.

“We haven’t had open-source evidence tested in a big way in the courtroom environment,” says Higgins, explaining that cases to come will be able to demonstrate its effectiveness.

With so many cases under investigation in Ukraine, prosecutors will have the opportunity to test the new type of evidence as they try to hold Russia to account.